Pixels to Product: Designing a Scalable Portfolio (Part 3)

In our previous essays, we explored simplifying portfolio design and the importance of writing in design. In part three, we’ll tackle the challenge of creating a portfolio that grows and adapts as your career evolves.

The challenge of relevance

Created with DALL·E

If your portfolio is over a year old, chances are it no longer represents how you actually solve problems today. I revisited my old case studies from Gridhaus — detailed breakdowns meant to demystify the design process for potential clients who were new to working with designers.

But since transitioning to product design, I’ve realised companies, founders, and product teams care less about seeing a perfect design process and more about whether you’ve solved similar challenges to theirs. A designer who has tackled comparable problems, even in a different context, is often more valuable than one who simply follows textbook design methods.

The shift in focus

As I moved into a lead role, I found myself stepping away from hands-on design to focus on guiding my team’s process. My days filled with reviewing work, equipping the team with the right tools, guiding decisions, attending project syncs, and planning priorities. While I missed having uninterrupted design time, seeing the team’s growth and success made it clear these were positive changes.

This transition gave me a broader perspective on what makes design valuable. It’s not just about crafting beautiful interfaces or following a perfect process — it’s about solving real problems effectively, whether they affect individual users, entire products, team dynamics, or company direction. This changed how I approach portfolio work.

Two projects, two lessons

When wearing multiple hats at growth-stage startups, the work extends beyond designing isolated flows or interfaces. Projects vary significantly in their challenges, with success depending more on key decisions and rapid iterations than perfectly adhered design methodologies. While schools and bootcamps suggest documenting every user interview, journey map, wireframe iteration, and UI component decision, this approach becomes unsustainable and often misses the point.

Instead, let me share two contrasting projects I worked on at my current role that demonstrate this reality:

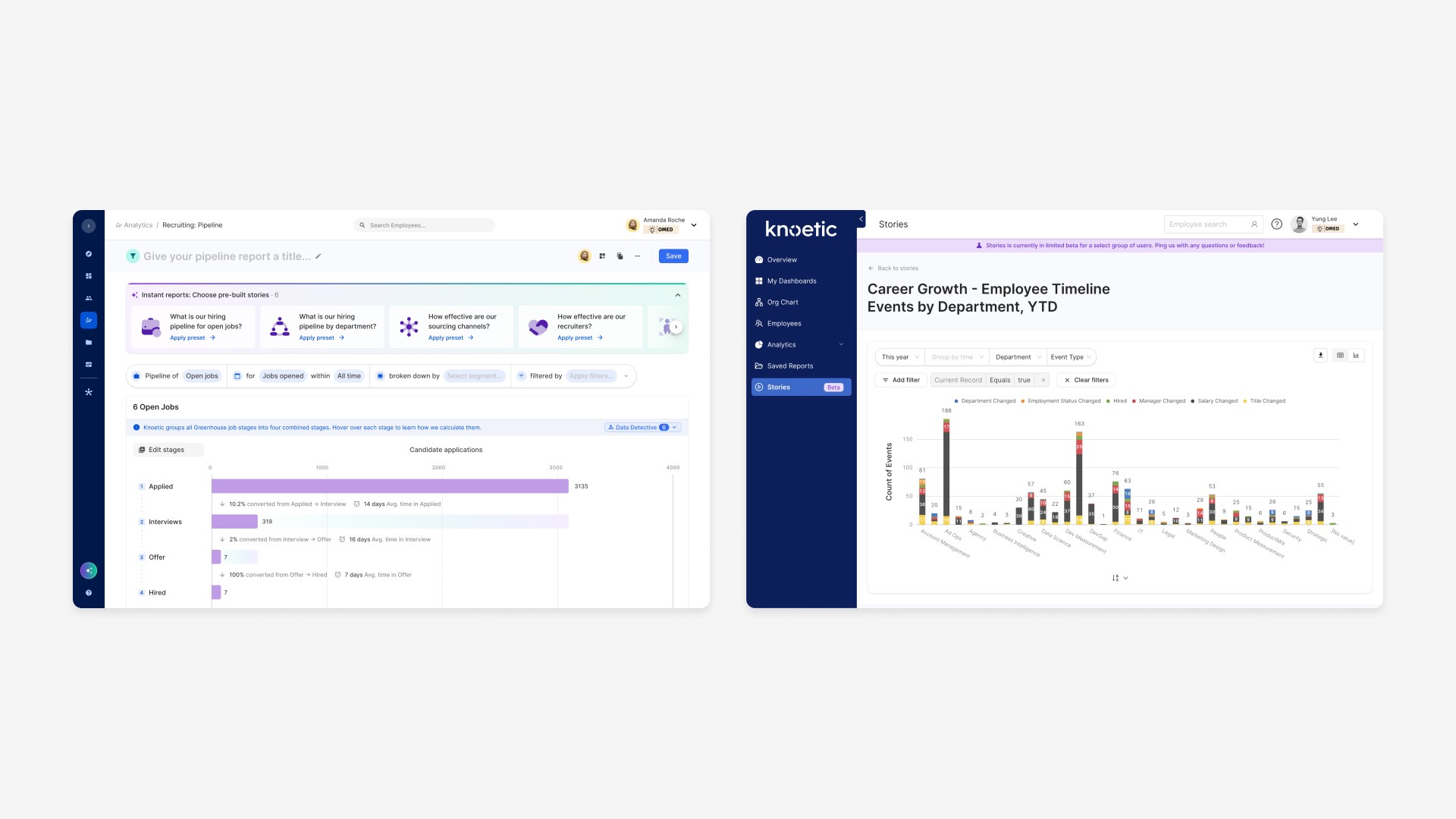

A recruiting analytics module: We aimed to help HR leaders understand their pipeline performance. Despite creating an intuitive interface through multiple iterations and user testing, the feature saw low usage because we hadn’t fully aligned our solution with users’ actual needs — they needed deeper insights than we could technically deliver.

A series of MVP tests: Here, we tackled the challenge of fragmented HR data. Instead of perfecting the design upfront, we rapidly shipped scrappy updates to users, learning and adapting based on their real needs. Each iteration clarified which problems were worth solving and which weren’t.

Can’t tell much by just looking at these two screens, can we? (Demo data used for privacy)

These examples demonstrate how the same work can be presented differently. Rather than focusing on the design process, I now emphasise what we tried to solve and what we learned about effective solutions along the way.

Rethinking the portfolio

This shift led me to reconsider my website’s content. I tried to avoid a common trap: creating a portfolio that spoke only to other designers rather than to the people who would actually use it. Here’s what I learned:

For past work existing as real products, I can simply link most of them from a list. Each project represents not just a design solution, but a challenge solved — whether it’s streamlining workflows, increasing engagement, or enabling better decisions.

The mental frameworks, reflections, and processes I used are best demonstrated through essays.

Take, for example, how we integrated generative AI into our workflow. We used ChatGPT to generate and refine hundreds of data field descriptions, review tooltips for complex metrics, and iterate on copywriting for user flows. Turning these tasks into repeatable prompts meant PMs and designers could spend less time writing, and we never needed to hire dedicated UX copywriters.

I’ve also plugged in entire data tables and asked ChatGPT to generate actionable insights for CPOs. What started as an internal workflow to create content for hi-fi prototypes evolved into a feature we shipped that provided real-time, accurate insights for our users.

This demonstrates something crucial about portfolio presentation: the most valuable insights come not from only showing what features we shipped, but from articulating how we identified opportunities, adapted our approach, and scaled solutions across the team. These learnings can’t be captured in a traditional project showcase format alone.

What started as experiments with AI tools evolved into fundamental changes in how our team worked. This kind of evolution in thinking and problem-solving is worth capturing. It’s less about individual projects and more about the patterns of problem-solving that emerge across different challenges.

Designed for thinking

A designer’s website doesn’t need to be a gallery of past projects. Instead, it can be a platform for sharing how you think about and solve complex challenges. We’re talking about real thinking with real results here — not “Design Thinking” frameworks that get packaged into worksheets and presentations, then swiftly forgotten.

As Austin Kleon aptly puts it:

“Writing isn’t just a way of communicating; it is a way to think about what you have to communicate.”

In my case, this means fewer polished mockups and more written exploration of:

Current challenges and how we’re tackling them

The evolving landscape of product design

The tech industry in our region

Retrospectives that connect past experiences to current solutions

This approach isn’t about claiming expertise. It’s about sharing experiences, questioning assumptions, and demonstrating pattern recognition across different challenges. I came across The Futur’s video: Planning a Personal Website: Does My Portfolio Matter? validating many of these same conclusions about moving beyond just showcasing work to demonstrating thought process and experience.

This mindset becomes critical as you progress in your career. A Junior Designer might impress by showing clean UI work and following good processes. But as a Lead or Senior Designer, demonstrating how you’ve solved increasingly complex problems becomes crucial. Someone who has solved the exact same problem your company faces is obviously valuable. But equally impressive might be someone who has tackled similar challenges in adjacent spaces, or solved more complex problems in different contexts.

The key is tuning your portfolio to reflect the depth of your problem-solving experience, not just the breadth of your deliverables. A Lead Designer showing only tactical execution without deep thinking raises eyebrows. Conversely, highlighting how your past experiences — even from seemingly unrelated projects — have prepared you to solve complex challenges can make you stand out, regardless of whether you’ve worked in that exact problem space before.

Hang Xu · How does a recruiter or hiring manager quickly determine whether to interview a designer?

Practical steps for new product designers

If we approach our portfolios with the same thoughtfulness we bring to product design, the path becomes clearer. Here are concrete steps to build a portfolio that demonstrates your problem-solving capabilities:

Focus on reflections: Move beyond showcasing finished products. Write about your approach to challenges and how learnings shaped future decisions.

Show real impact: Frame your work through outcomes that matter. Apart from listing features shipped, demonstrate whether your solutions affected key metrics, user behaviour, or team efficiency.

Connect the dots: Help readers understand the patterns in your work. Show how solving one challenge prepared you for tackling others, even across different domains or industries.

Document decisions: Share the key choices you made and their rationale. My practice of maintaining decision logs in PRDs has helped me recall my thought process.

Create a resource section: Compile articles, notes, and other resources that inform your domain expertise.

Build in public: Use your portfolio as a living document. Regular writing about your current challenges and approaches shows active growth and critical thinking.

Keep it authentic: Share both successes and painful lessons. Your journey and perspectives matter more than following a standard template.

They all point to a shift in how we should think about our work: instead of cataloging the past, focus on demonstrating growth. Rather than asking yourself “What did I do,” ask “What problems have I learned to solve better?”

Looking ahead

While we advocate for user-centred design in our work, we should apply the same principle to our portfolios. If we carefully consider user needs and context when designing products, it’s a shame to create portfolios that serve our own preferences rather than our audience’s needs.

A portfolio should be approached like any other design challenge:

Who is the user? (Hint: Often not other designers)

What are they trying to evaluate? (Your ability to solve relevant challenges)

What context are they operating in? (Limited time, specific needs, varying design knowledge)

The future of design portfolios isn’t about documenting process or showcasing every project. It’s about demonstrating your ability to recognise patterns and apply your problem-solving capabilities effectively across different contexts. This mirrors exactly what we stand for in our product design work.